Alarm bells are ringing in Tokyo, Seoul, and Washington over Kim Jong Un’s transactions during his 6-day stay in Vladivostok. He visited a full range of Russian military installations—bases, missile sites, ports, space port. Kim seemed to have a particular interest in space technology, no doubt due to the failure of two recent space launches.

From various reports, the transactions will take place in two directions. Russia will probably provide North Korea with help on missile technology, notwithstanding UN sanctions on the North’s ballistic missile tests. Russia may also provide food assistance to offset North Korea’s always troubled agriculture sector, and it may increase the number of workers it sends to North Korea. North Korea is likely to provide Russia with a variety of weapons, including multiple rocket launchers, artillery shells, sniper rifles, drones, and missiles.

It’s generally believed that Russia, despite the depth of its military industries, badly needs basic war supplies such as artillery shells. But China has been a reluctant supplier, largely leaving the field to Iran and North Korea. (Keep in mind that South Korea recently agreed to start selling arms to Ukraine. And South Korea has become a major military-industrial partner of Poland, drawing a warning from Vladimir Putin last year.)

North Korea suddenly is the darling of Russian and Chinese diplomats. In July, Russia sent its defense minister Sergei Shoigu to visit North Korea, the first time since Soviet days that a Russian defense minister had visited North Korea.

Following on Kim Jong Un’s trip to Vladivostok, China’s foreign minister Wang Yi went to North Korea, and Russia’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov did the same. The substance of those visits has not been revealed, but they probably are not just an initiative to bolster their partnership.

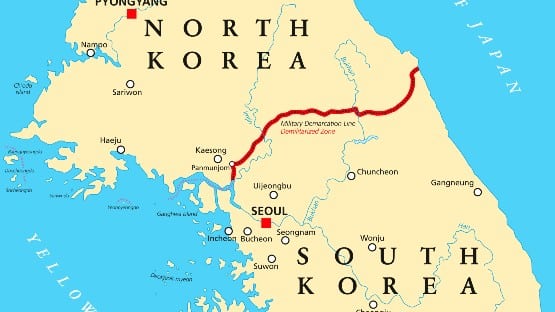

They probably are also in response to three developments: the recent trilateral agreement of South Korea, the US and Japan to deepen security cooperation; a new round of meetings of US and South Korean defense officials on deterring North Korea through the recently created Nuclear Consultation Group; and high-level talk in South Korea, though restrained by Washington, about developing its own nuclear weapons.

Thus, implicit nuclear threats are being made by both Koreas. Consider this report in the South Korean press on a joint US-ROK statement after a visit by a US defense department official: “the U.S. side reaffirmed its ‘ironclad’ commitment to the defense of South Korea, leveraging the ‘full range’ of its military capabilities, and reiterated that any nuclear attack by the North against the U.S. and its allies will result in the ‘end of the Kim regime’.”

Alternative Views

Will new North Korean ballistic missile tests or even a long-awaited seventh nuclear test be in the offing? Has the threat from the North risen to a new level? Most US and South Korean analysts seem to think so, but here are some other ideas.

Two people with considerable experience dealing with North Korea, Robert Carlin and Siegfried Hecker, go deeper into the Kim visit to Russia. They write that “it is the result of a fundamental shift in North Korean policy, finally abandoning a 30-year effort to normalize relations with the US.”

Contrary to the conventional view of North Korea, these experts argue that even as Kim invested heavily in nuclear weapons and missiles, he also looked to use them as bargaining chips with the US, hoping he could win security assurances as part of normal relations. But Kim finally concluded after his dealings with Trump and lack of attention by Biden that normalization wasn’t achievable.

At that point, he moved closer to Moscow and Beijing. A missed opportunity for the US? Perhaps; and as with US relations with Iran, the war in Ukraine has so absorbed the attention of Washington policy makers that creative diplomacy aimed at keeping nuclear weapons in their silos just isn’t receiving attention.

From another angle, Kim’s Russia visit may pose problems for China. Russia may have gained an advantage over China by becoming the key weapons supplier to Pyongyang.

Kim used the occasion to reiterate support of Russia’s war on Ukraine, saying for instance: Russia would “win a great victory in the sacred struggle to punish the band of evil that aspires to hegemony and feeds on expansionist illusions.” An expected tribute to Russia, to be sure, but perhaps something more.

Greater Russian influence in North Korea might lead to more missile tests by Kim and further tension on the Korean peninsula. Putin might find that helpful as the Ukraine war moves along, but the Chinese have always been concerned about a crisis on their doorstep precipitated by a North Korean weapons test.

Given their domestic problems and tensions with the US today, a crisis on the Korean peninsula would seem particularly unwelcome in Beijing. I would have to think that view has been communicated to Kim Jong Un and the Russians more than once.

If US relations with China were better, China’s cooperation in restraining Kim Jong Un could be counted on. That’s not the case, and thus another missed opportunity for lowering tensions.

Mel Gurtov, syndicated by PeaceVoice, is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Portland State University.