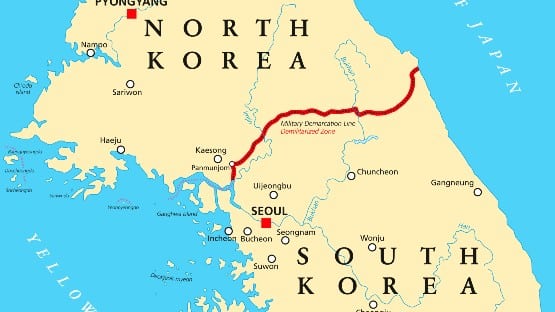

Two of America’s most prominent North Korea experts, Robert Carlin and Siegfried Hecker, begin their latest analysis with this sentence: “The situation on the Korean Peninsula is more dangerous than it has been at any time since early June 1950.”

They believe Kim Jong Un has decided to “go to war.” Unlike past years, recent belligerent North Korean statements don’t appear to be bluster. If these experts are right, the longstanding U.S.-South Korean strategy of nuclear deterrence is failing.

In their view, Kim has abandoned North Korea’s long-sought effort to normalize relations with the U.S. He is now willing to challenge the U.S.-Republic of Korea strategy that relies on Kim’s rationality—his understanding that war would mean the total destruction of his regime and his country.

Why now? What accounts for this extraordinary shift in North Korean thinking?

Carlin and Hecker contend that it entails, first, the North Korean belief that “the global tides were running in its favor,” due to the US being bogged down in Ukraine and the Middle East; second, that unification with South Korea is impossible, and that North and South Korea are now belligerent nations; third, that North Korea can rely on Russia for support.

Are these experts right? A surprise attack on South Korea would seem like madness. But Kim Jong Un’s strategic calculation may be that with the US weighted down by military commitments elsewhere, and North Korea now possessing the capability to reach the mainland US with a nuclear weapon, his country can deter a U.S. nuclear response to a North Korean attack.

In doing so, he not only risks the end of his regime but also a regional war that would involve China and Japan. The possible destruction in such a war is unimaginable.

Problems with U.S. policy

I have no idea if Carlin and Hecker are correct. They rely on years of experience and a close reading of official statements, not hard evidence.

I think this much is clear: For many years, through three generations of the Kim dynasty, the U.S. has failed to take seriously North Korean interest in obtaining security assurances from the U.S. in return for abandoning a nuclear weapons buildup.

In recent times, Donald Trump had an opportunity at his 2019 summit meeting with Kim in Hanoi, Vietnam, to make a breakthrough in relations with the North. But Trump refused to bargain on removing US sanctions and left the negotiating table, quite possibly making Kim Jong Un feel humiliated.

Joe Biden has been overwhelmed with other foreign policy issues. His administration has paid North Korea minimal attention beyond the usual criticism every time the North carries out a ballistic missile test. Thus, Carlin and Hecker may be right that Kim has given up on an engagement strategy and is now willing to go for broke.

The China factor is also important here. If the U.S. and China were on better terms, Beijing might be willing and able to intercede to ensure that its putative ally, North Korea, does not carry out military action that would endanger China’s security no less than South Korea’s or Japan’s.

Chinese leaders may not be aware, or don’t believe, that North Korea is preparing for war. How much influence China actually has with Kim is uncertain; U.S. analysts have often exaggerated it. Still, active US consultations with China are essential to help avoid a catastrophic decision by the Kim regime.

A new U.S. policy approach

U.S. policy on North Korea over the last few decades has changed little. It seems to come down to just three points: gain North Korea’s agreement to denuclearize and only then discuss sanctions relief and security issues; back UN sanctions and criticism to stop North Korea from conducting ballistic missile and nuclear-weapon tests; and rely on nuclear deterrence to prevent a North Korean aggressive act against South Korea or any other state. These points, shared by Democratic and Republican administrations alike, are clearly insufficient and, if Carlin and Hecker are right, no longer relevant to strategic thinking in Pyongyang.

Biden administration officials have said in the past that the U.S. is prepared to enter into talks with North Korean without preconditions. That’s fine, but the current situation calls for a reappraisal of longstanding policy.

Relying on forward military deployments in South Korea and Japan to contain North Korea is not enough. It is long past time to reactivate diplomacy with North Korea and put incentives for tension reduction on the table.

Those should include acknowledging the North’s legitimate security concerns, accepting it as a nuclear power, and understanding the mutual (and regional) benefits of normalized relations. North Korea is not going to give up its nuclear arsenal, but the right package of incentives may persuade Kim Jong Un to warehouse his weapons, put a moratorium on ballistic missile tests, and open the door to monitored economic and humanitarian aid.

At the least, the U.S. needs to test Kim’s interest in engagement. Now.

Mel Gurtov, syndicated by PeaceVoice, is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Portland State University and blogs at In the Human Interest.