By Karl Blankenship

Bay Journal News Service

A long a dusty road in Tioga State Forest near the northern edge of Pennsylvania, a sign marks the remains of Camp Leetonia. A picture shows a scene from nearly a century ago: a cleared field lined with military-style barracks and other buildings.

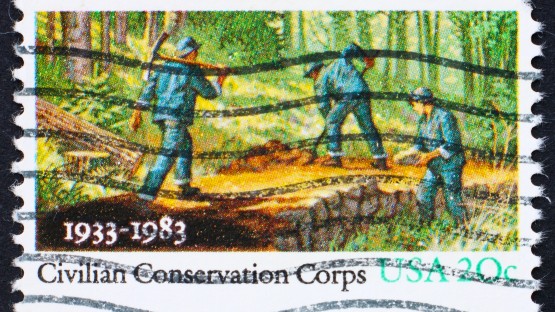

Camp Leetonia wasn’t a military installation. It housed a company of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “tree army,” better known as the Civilian Conservation Corps.

As I visited state and national parks over the years, I vaguely knew that I used rustic log picnic pavilions or other buildings built by impoverished young men during the Great Depression.

Over time, I became increasingly aware of how this organization, which existed less than a decade, shaped outdoor experiences for myself and millions of others. I hike, often unknowingly, on trails forged by the CCC. I stay in campgrounds, eat in pavilions, drive on roads and relax beside reservoirs built by the CCC. In places such as Yorktown and Jamestown, I visit historic earthworks, trenches and buildings that exist thanks to the work of segregated Black CCC crews.

The roots of the CCC stem from a reforestation program that Roosevelt — a lifelong champion of improved forest management — launched as New York governor in 1932 to fix landscapes suffering from decades of abuse.

Others had advocated for a citizen army to aid conservation but “the spirit of the CCC, including many of its organizational details, was entirely concocted by Roosevelt,” wrote historian Douglas Brinkley in his book, Rightful Heritage.

Roosevelt’s request for the program cleared Congress in 10 days. Barely two weeks later, on April 17, 1933, Camp Roosevelt — the first of 2,514 camps — opened in the George Washington National Forest in Virginia.

At the time, the unemployment rate for adult men was at 25%. And by July, more than 250,000 young men, referred to as CCC “boys,” were enrolled in hundreds of camps. Over the next decade, roughly 3 million would serve.

Enrollees were paid $30 a month. They usually sent $25 home to help their families, almost all of whom were on public relief. They signed up for six-month periods that could be renewed up to two years. Typical recruits had an eighth-grade education, but camps had libraries and incorporated classes to bolster education. For many, having three meals a day was novel. The average enrollee gained 12 pounds.

Each camp was organized into a company of about 200 men and included barracks and officers’ quarters, as well as a mess hall, recreation hall, educational building and other structures. U.S. Army officers were in charge, while foresters, carpenters and other professionals guided the work.

The CCC may be best known for planting 3 billion trees, but recruits also constructed fire roads, lookout towers, bridges, hiking trails, cabins, picnic pavilions, fishing piers and dams. (Roosevelt thought all state parks should have a lake or swimming pool.) They fought forest fires and stocked fish. In agricultural areas, including the Chesapeake Bay watershed, recruits worked to control erosion.

The CCC’s accomplishments are everywhere, including much of the original infrastructure for Shenandoah National Park, where recruits planted trees and built campgrounds, picnic areas and hiking paths. They helped construct Skyline Drive, including overlooks and stone walls.

But they also undertook tasks people know little about — even when the results are in plain sight. Four Black companies worked at the newly established Colonial National Historical Park from 1933 through 1941. They did archaeological work in Yorktown to identify trenches, fortifications and foundations of historic buildings. They also reconstructed earthworks on the battlefield where Gen. George Washington’s victory effectively ended the Revolutionary War.

“In the 1930s, there wasn’t much to look at as far as the battlefield goes,” said Dwayne Scheid, an archeologist with the park. “Most of the remaining earthworks at that time were related to the Civil War because, after the [Revolutionary War] siege ended, Washington ordered most of the earthworks removed. So the landscape looked totally different.”

Black CCC crews worked on the Colonial Parkway, which connects Jamestown, Yorktown and Colonial Williamsburg, planting trees and making other improvements. They made many of the cannon reproductions on display at Yorktown.

National Parks were not the only beneficiaries. Roosevelt also put a high priority on creating “localized recreational opportunities.”

Virginia had only two state parks when he became president. Within three years of the CCC’s creation, and thanks to 107,000 enrollees, six were added: Douthat, Westmoreland, Hungry, Fairy Stone, Staunton River and Seashore (First Landing).

In Maryland, the CCC worked on Swallow Falls, Herrington Manor, New Germany, Big Run, Cunningham Falls, Cedarville, Fort Frederick, Washington Monument, Gambrill, Patapsco Valley, Elk Neck and Pocomoke River state parks. They also restored two massive, historic stone structures: Fort Frederick and the state’s Washington Monument.

In Pennsylvania, dozens of state parks benefitted. The public responded, with visitation jumping from 2 million in 1930 to 9 million in 1935.

Few were more pleased by the CCC than Pennsylvania Gov. Gifford Pinchot. Pennsylvania was second only to California for its number of camps, and Pinchot chose many of his state’s 151 camp locations himself.

Pennsylvania crews racked up impressive work. Joseph M. Speakman, author of At Work in Penn’s Woods, credits recruits for stringing 791 miles of telephone lines, building 3,386 miles of truck trails and 3,483 miles of foot and horse trails; planting more than 63 million trees; constructing 102 dams; operating tree nurseries; clearing 31,585 acres of forest fire hazards; and stocking 1,783 fish-rearing ponds.

They fought forest fires — sometimes losing crew members — and built forest fire observation towers. Acreage lost to forest fire in the state dropped by half within 5 years.

“Today, virtually every state forester or park manager in the country would drool at the prospect of having the labor of 200 men available to them for their ever-behind work needs,” Speakman wrote.

The CCC was intended to be racially integrated — initially, some camps were — but by 1935 all camps were segregated to maintain the support of conservative southern Democrats. Camps were male-only despite First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s pleas for counterparts to benefit unemployed women.

Congress defunded the CCC in 1942 with the onset of World War II, but many think the country would have benefited from its continuation. “The CCC is probably one of the most, if not the most, popular government programs ever created in terms of public perception,” said Joshua Roth of the Pennsylvania Lumber Museum, which has an extensive exhibit on the corps. “When we do CCC programs, the number one thing that people say is, ‘I don’t understand why they still don’t do that today.’”

The Chesapeake Conservation Corps, Pennsylvania Outdoor Corps, Maryland Conservation Corps, Virginia Service and Conservation Corps, and other similar programs all have their roots in the concept, though none approach its scale.

The impact of placing nearly 3 million young men over a nine-year period in the nation’s forests, farms and parks was impressive. The signs of their work are everywhere, along with scattered memorials and museum exhibits.

But as I looked at the sign marking the site of Camp Leetonia, once deeply scarred by decades of abuse, I thought the most fitting memorial was right behind it: a healthy forest where the CCC camp once stood.

Karl Blankenship is the founding editor and now editor at large of the Bay Journal. This article first appeared in the October 2022 issue of the Bay Journal and was distributed by the Bay Journal News Service.