[email protected]

Thelma Newman remembers the anticipation of a late 1980s documentary produced by WVPT on the history of Staunton. Her father-in-law had been among those interviewed for the film, for one thing.

The hopes of Newman and others in the Staunton African-American community that the film would do their contributions to the history of the Queen City justice were dashed at its premiere, though.

“The only thing that they showed of the African-Americans even participating in the City of Staunton or even that they were in the City of Staunton was that my father-in-law spoke of going down to the Wharf area to get watermelons, and that Mr. Tate used to go downtown to buy baseballs and bats,” Newman told me.

I was aghast, probably not as much as she was 20 years ago, but still.

“Oh, I was angry. No, I wasn’t angry. I was mad,” Newman said, hovering over the final word for emphasis.

Fast-forward 20 years, to the upcoming premiere of “Staunton’s Other Park,” a documentary on the history of Montgomery Hall Park, which served as the de facto public park for African-Americans in Staunton and the surrounding area until 1969, and let’s just say that it’s a far cry from watermelons and ball.

“It’s important so that the young people understand what it was like. We were not allowed to go to Gypsy Hill Park. Well, we could go one day a year. They set that aside for us to go. But other than that, you could walk by and look in, but you couldn’t go,” said Staunton resident Rita Wilson, who was among those interviewed for the documentary, which was produced by the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library and the Staunton-based Virginia Media Group.

The film will have its debut screening, appropriately enough, at Montgomery Hall Park at the annual Montgomery Hall Park Lawn Party on Saturday at 3 p.m.

The 19-minute documentary tells the history of Montgomery Hall Park in the Jim Crow era, and doesn’t pull any punches in doing so. “It tells the true story of how things were during the Jim Crow era. And it will also hopefully bridge the gaps for African-Americans for generations to come. Our young people today have absolutely no knowledge of the segregation era. And that may not be a bad thing in some respects, but it’s important to know just how far the African-American community has come,” Newman said.

How far things have come, indeed. “When you talk to some young African-American people today, they can’t believe that there were signs on doors that said, Colored Only, or White Only, or what have you. They can’t believe that Gypsy Hill Park was a restricted, off-limits place for African-Americans except for the one day a year that they were permitted to go there,” Newman said.

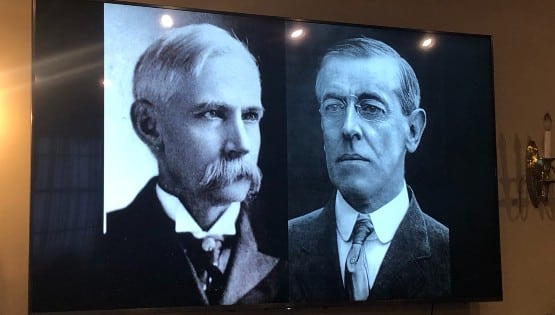

That the presidential library of a man who continued segregation policies in his administration, Woodrow Wilson, would be involved in such a project speaks to the sensitivities felt on the library staff. “We’re a bit self-conscious about that, to be honest with you. And so we say, Well, what can we do to make up for that?” said Joel Hodson, the director of education at the library and the point person on the staff on the film project.

Jason Levin at Virginia Media Group, another important person in the making of “Staunton’s Other Park,” earned points with Newman for his editing and production work on the documentary. “I am very well pleased with the idea that persons were permitted to talk, and none of it was editorialized. Because sometimes when someone else is translating something, you lose something in the meaning. But this was done in such a way that the people that lived the park, worked at the park, played in the park, told the story as they remembered it in their own way,” Newman said. To Levin, that was just the way the story needed to be told. “We let the people tell the story themselves. We limited the narration to brief historical facts about the era. We wanted it to be an oral history told by the people that were there, that experienced it. We let the interviewees tell their story, and let their memories serve as the history,” Levin said.

Wilson’s memories of Staunton’s other park are bittersweet. “It was a special place. It was a meeting place. And especially after they put the pool in. It was a nice meeting place for Stauntonians, and they weren’t many pools, I don’t know that there were any in this vicinity. So you had busloads that came into the park. Lynchburg, Lexington, Roanoke – church buses came from as far away as Roanoke. The park would be just full of people on Sundays,” said Wilson, who recently retired from Staunton City Council after serving 17 years on the local governing body.

That’s the sweet part. The bitter – “There are people now who still don’t go to Gypsy Hill Park,” Wilson said. “They say, Didn’t want us over there then, so we’re not going now. And I don’t have any statistics to prove this, but I’d bet more white people use Montgomery Hall than black people use Gypsy Hill. I don’t have anything to prove that, but if you go to Gypsy Hill, you don’t see many African-Americans over there.”

It’s good to get this out there, I think – the whole story, the good memories, the lingering questions as to why things had to be the way they had to be.

“This is a documentary showing the Old South the way it really was right here in our own dear town of Staunton, Virginia. And I’m hoping that this will just be the beginning of the true story of the history of Staunton,” Newman said.