The case of Vector Industries is one where I unashamedly wear my heart on my sleeve.

I designed and maintain the Vector Industries website. I handle the company’s marketing and PR. I consult with execs on various aspects that could fall under the rubric of strategy.

That now clear, I am proud to be on the team, for a number of reasons.

First and foremost, that mission. Vector currently employs in the neighborhood of 100 people. Technically speaking, Vector is what bureaucrats call a “sheltered workshop,” because the rules of the workplace are different than in what the bureaucrats call a “competitive integrated environment.”

What that means at Vector is a shorter workday, more breaks, a little more relaxed atmosphere.

But make no mistake, it’s work, and Vector is as competitive and integrated as any other business.

On the competitive side, Vector’s clients include Bold Rock, Devils Backbone, Federated Auto Parts, Parker Bows and Reynolds, to name a few.

And the work they do for those clients isn’t charity. We’re talking assembly, packing, fulfillment like you’d see from any other light manufacturer and logistics company.

On the integrated side, the composition of the employee base is a mix of people with and without disabilities, working side by side.

Walk around the 80,000-square-foot facility on any given workday, and there’s no way you wouldn’t think this was any other bustling business running at breakneck pace trying to keep up with a dizzying pace.

It means more to me and folks who know and love Vector and what it does for the community because of the fact that Vector exists to provide job opportunities for people who otherwise would be left on the outside looking in.

People like Amy Sorgen, who lives with muscular dystrophy, and had a job in the competitive workforce for more than a decade before her health issues forced her out.

Her father, Bob, a federal retiree, connected Amy with a job counselor who tried for more than a year to help her land a new job, to no avail.

The Sorgens found Vector in 2004, “and they hired her immediately,” Bob Sorgen said.

Amy works several hours a week at Vector.

“I’m so grateful for Vector,’’ her father said. “It has created a purpose for Amy, and a feeling of independence and pride.”

I get to hear (and write about) similar stories about what Vector does for people with disabilities and their families all the time. That’s the advantage of being on the shop floor a couple of days a month. I’m not forming impressions based on written reports and studies and analyses.

Back to the bureaucrats. You knew it was coming. That word carries a negative connotation, and in the case of stories like Vector, it’s deserved.

If you know me, you know that I wear my heart on my sleeve in myriad ways, as I mentioned above in reference to my feelings on Vector Industries, and the now on me being an unabashed political liberal.

So when I write here that the liberals have it all wrong with their push to close down so-called sheltered workshops like Vector, yeah.

The thinking among liberals seems to be that people with disabilities are being exploited working at places like Vector Industries, and I get what they’re saying, no question.

I interviewed a Vector parent a few years ago who told me that when he and his wife and son lived in another state, they found a job for their son at a sheltered workshop that was no more than busywork created to meet the requirements of a federal grant.

I’ve also found in my research stories of workshops that have their employees with disabilities literally sifting through garbage for glass and aluminum to sell to recyclers.

The first example is wasteful, the second, yes, exploitative.

No question, we don’t need those kinds of workshops.

But what I wrote earlier about getting out from behind a desk reading reports and getting out onto the shop floor seems to apply with Vector and its many sister non-profits who do it right.

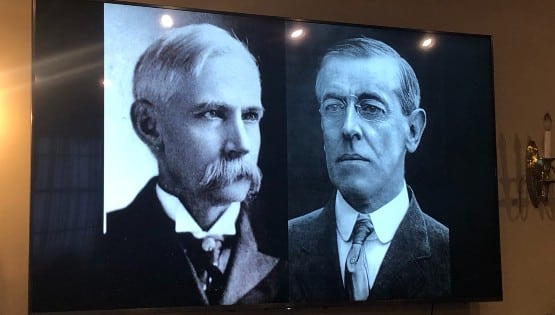

This is one area where the Obama administration, and the McAuliffe administration here in Virginia, could do a lot better.

Congress passed something called the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act in 2014, a law described breathlessly on the Department of Labor website as “landmark legislation that is designed to strengthen and improve our nation’s public workforce system and help get Americans, including youth and those with significant barriers to employment, into high-quality jobs and careers and help employers hire and retain skilled workers.”

The law got its teeth in 2016 with federal regulations put in place by Obama’s DOL.

The relevant portions of WIOA to so-called sheltered workshops like Vector: where the law limits placements at sheltered workshops and other work environments where people with disabilities earn less than minimum wage.

Sub-minimum wage employment is open not only to sheltered workshops, but any company with what is called a 14(c) certificate under the federal Fair Labor Standards Act.

Wages under a 14(c) certificate are based on worker productivity. The idea behind 14(c) is to open up job opportunities for people who might otherwise not be able to gain and hold down work, in a competitive environment or otherwise.

Proponents highlight the psychosocial benefits to people with disabilities being able to gain employment, contribute to the workforce and take home a paycheck, the benefits to their families to have their loved ones working and contributing, and not in adult daycare.

Critics of 14(c) refer to the sub-minimum wage jobs as being exploitative by nature.

The critics are in ascendance with WIOA and the 2016 regulations. Vector Industries noticed in 2017 that it had suddenly stopped getting referrals for prospective new employees from the state Division of Aging and Rehabilitative Services, and asked me to look into what may be going on.

I ended up getting a few minutes on the phone in February with Kathy Hayfield, the director of the Division of Rehabilitative Services.

Hayfield made it clear from the outset that the sudden cessation of employee referrals was no oversight.

“Federal laws have changed such that our federal vocational rehabilitation program dollars cannot be spent to support people in segregated work settings. Let me flip that around. Our dollars must be spent to support people in competitive integrated employment, and those are the key words of the day,” Hayfield told me.

In the post-WIOA environment, “organizations like Vector whose primary purpose in life is to employ people with disabilities are under much more scrutiny, and they’re going to have a harder time surviving, unless they change their model to focus on placing people in the community in jobs where they work with people who do not have disabilities,” Hayfield said.

I’ll interject here: Vector Industries isn’t looking for a hand out from DRS to be able to survive. Chrissy Johnston, the CEO at Vector, said the issue that her management team faces is not having enough employees to do the work that its clients send its way.

Vector is down roughly 25 employees since 2016, a direct result of the DRS move to stop referring people with disabilities to seek employment there.

Ostensibly, the DRS is referring those prospective employees for jobs elsewhere, right? Um, well …

“A person who is making a very low sub-minimum wage might benefit more from a community-integrated day-support program versus a sheltered workshop work program where they’re making very low wages. You could argue this so many different ways philosophically,” Hayfield said.

Yeah, yikes.

That’s what this comes down to. We’re arguing this philosophically, based on reports and studies and analyses.

“People with disabilities have to be doing the same jobs as people without disabilities, and they have the same opportunities for advancement and promotion, and wages are the same,” Hayfield said. “Very often, sheltered workshops will pay the people with disabilities sub-minimum wage based on their productivity, but then they’ll have people without disabilities there who aren’t being paid in the same manner.

“That person who is being paid that sub-minimum wage could get a job in the community working at a Kroger making minimum wage or above just like another bagger on a line is making.”

Which is fine, if grocery stores actually hired people to bag groceries all day. I worked grocery jobs in college, and bagged more than my fair share, in between stocking shelves, unloading trucks, doing maintenance and cleaning.

The assumption of bureaucrats is that private employers will out of the goodness of their hearts create low-intensity jobs for people with disabilities and pay them the prevailing wage or better with unicorns riding off into a rainbow sunset as the backdrop.

You actually hear this (without the unicorns and the rest) at conferences from these folks. Employers will take them in, and their co-workers will befriend them and give them rides to and from work, which only works if managers schedule accordingly, which of course they can’t, because they’re running actual businesses, not case studies thrown together by people who have no idea what a competitive integrated environment looks like, much less how it operates.

Here’s where your resident liberal Democrat now tells you that he admires the hell out of three very conservative Republicans who got out from behind their desks and spent a couple of hours on Monday on the shop floor at Vector Industries to see how the real world works.

Steve Landes, Dickie Bell and Ben Cline are members of the Virginia House of Delegates representing swaths of the Shenandoah Valley and Central Virginia.

I could cynically point out that all three are up for re-election this fall, and that their interest in Vector could be about getting in front of TV cameras to show themselves as caring, stand-up guys.

But then, I’d also have to concede if I did that, seriously, disability employment as a sexy campaign issue, in 2017 America?

“When you see what they’re facing here at Vector, it’s pretty clear that the way the Division of Aging and Rehabilitative Services is interpreting the federal rules is hampering the mission here. We have to figure out a way where we can get things back to the point where they can refer individuals to this facility and facilities like this around the state,” Landes said.

Which is easier said than done. The changes at the state level were made in line with the regulations handed down by the Obama administration.

I don’t read the situation here, though, as being entirely top-down. Virginia could inject some common sense into its approach to complying with WIOA and the Obama-era regulations bringing it into the real world and still refer prospective employees with disabilities to jobs at places like Vector Industries.

And in fact, as Landes points out, the state may have incentive to seek out a new middle ground.

“Doing this is more beneficial to the state because the state Medicaid waiver program is very expensive,” Landes said. “Those are important services that those individuals need, but if the individual can work part of the day or part of the week, that means they’re not in a day placement, which is expensive, it means their family members don’t have as much pressure to take care of them, so they can go to work or have respite. It really benefits everyone.”

Bell was a special education teacher in the Augusta County school system for 10 years before being elected to the House of Delegates in 2009. As he toured the Vector Industries facility, he ran into a former student working in assembly and had a nice moment with her.

“They’re doing a productive job. They’re productive citizens. And they enjoy doing it,” Bell said after the tour. “Why in the world we’re not embracing it with both arms is beyond me. But that’s our job as legislators. I don’t know if there’s a legislative fix, but we’re going to find out what’s going on, and at the very least apply some pressure.”

Cline joined the facility tour about midway through – he had a court case to take care of and rushed up Interstate 81 to join us late.

And then the only media person he talked to at the end was me, so if he was there to play politics for the cameras, he didn’t do a good job there.

“These are hard-working citizens meeting the needs of local businesses, and doing it in a fantastic way. The quality is top-notch. And the workers are happy. For the federal government and the state government to steer away from this type of operation is discouraging. We want to reverse that trend. We want to bring employees back to facilities like this, instead of forcing them to sit at home with nothing to do, and a declining quality of life,” Cline said.

People with disabilities deserve the opportunity to be able to bring home a paycheck, to be able to contribute to the economy, to society, and despite the best of intentions, the Obama-era WIOA gets it dramatically wrong, to the point of making life harder for the very people that the law was meant to empower.

If you want to see this in action, let me know, and I’ll take you on a tour of Vector Industries, so you can see it for yourself.

Column by Chris Graham