Two years after graduating from Waynesboro High School, Reggie Harris was taken by the Oakland A’s in the 1989 Rule 5 draft, and he made the team – the defending World Series champs – out of spring training in 1990.

“I’m just watching the previous World Series that year, in ’89, the earthquake series with San Francisco, and two weeks later, I’m on that team,” said Harris, who joined me to talk about his baseball career on the “Street Knowledge” podcast this week.

“In spring training, I walk in the clubhouse, must have took me two hours to put my clothes on, watching these same people,” Harris said. “I’m just in high school two years before that, and I’m watching these guys, and everybody’s over 30 years old, I’m the youngest guy in the whole clubhouse. I’m like, you gotta be kidding me. I just pinched myself.”

Harris was a two-sport star at WHS – a four-year starter in basketball, where he is the school’s all-time leading scorer and first-team All-State as a senior; and in baseball, he was a two-time All-State selection, the Gatorade Player of the Year, and he finished with a sterling 24-3 record on the mound.

The question with Harris, starting in his sophomore year at WHS, was: which would he pursue – basketball or baseball?

Ideally, he wanted to do both, at the college level.

“It was crazy. A whirlwind,” said Harris, recounting the full-court press from college recruiters – two sets: hoops and baseball.

“I can’t imagine what it is now with the social media. There wasn’t any social media back then, and it was still crazy. They just called your house at all hours of the night. Didn’t matter,” Harris said.

He decided in his junior year that he was going to sign with Virginia Tech, which was recruiting him with the promise that he could play both sports – as the school had allowed another local two-sport star, Dell Curry, to do.

Curry went on to become Tech’s all-time leading scorer on the hardwood while going 6-1 with a 3.81 ERA on the mound, and having his name called in the 14th round of the 1985 MLB Draft by the Baltimore Orioles, before ultimately deciding to pursue an NBA career, which turned out OK for him – he scored 12,670 points in 1,083 games across 16 NBA seasons – and later, his sons, Steph and Seth.

For Harris, making the call to commit to Virginia Tech made things slightly less crazy, though there was the matter of the radar guns behind home plate at his baseball games his senior year.

“Pretty much, you got 25 pro scouts with the radar guns. It got kind of intimidating sometimes,” Harris said.

Baseball would throw Harris a curveball as his senior year wound down – he was taken with the 26th pick in the first round of the 1987 MLB Draft by the Boston Red Sox.

This is the same draft in which future Hall of Famers Ken Griffey Jr. (first) and Craig Biggio (22nd) went ahead of him.

Other names from that first round that caught my eye: Jack McDowell (1993 AL Cy Young winner), Kevin Appier (169 career MLB wins), Travis Fryman (223 career MLB homers).

Suddenly, Harris had a choice to make.

“I was all packed up and going to Virginia Tech. Already had my classes set up. I got there on a Friday. Classes started on a Tuesday,” said Harris, who signed for a $92,500 bonus – 2025 inflation value: $264,471.83.

“I gave them a certain number to get to, and I told them, if they get to it, I would give it a go,” Harris said. “Tech was on board. I told them, if I they come to that number, and I would go, would they leave the door open, and then we come back in a year or two with eligibility for basketball, and that was on the table. And I said, OK, I can’t lose in this deal. Yeah, they met the number, I signed that Sunday.”

His first couple of years in the minors were rough.

“I had to learn how to pitch,” said Harris, who had a 95-mph fastball in high school. “I could just throw the ball by people. Once guys realize you had one pitch, you got to develop another one, and it took me a couple years to develop it.”

His first season, in Low-A ball, he finished with a 2-3 record and 5.01 ERA. In 1988, Harris split his time between Low-A Elmira and High-A Lynchburg, he was 4-14 with a ghastly 6.46 ERA.

In Year 3, 1989, “everything started to click and come around,” Harris said – and he went on to post 10 wins and a 3.99 ERA in 29 starts.

The Red Sox front office, here, made a strategic blunder, leaving Harris off the 40-man roster ahead of the Rule 5 Draft.

“They thought they could slip me through because I had two rough previous years, and Oakland grabbed me and took a chance,” Harris said.

From spending parts of three seasons at Low-A and High-A, Harris was suddenly on the star-studded “Bash Brothers”-era A’s – Mark McGwire hit 39 homers, Jose Canseco had 37; future Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson had 28 homers and 65 stolen bases.

“My locker in the clubhouse was right beside Rickey’s, so I was there to hear all the media interviews, all that stuff. I learned how to deal with the media, this and that, from him, just how to present yourself,” Harris said. “Some of the things he said, you can just laugh, but he ended up being one of my best friends in baseball. I stayed in contact with him to the day he died. He had his Ricey- isms, as you already know. He was the type of guy that would come to the clubhouse and tell you what he’s going to do before he did. He’d say, I might hit me a leadoff home run, steal a couple bags. First pitch of the game, he’d hit one out. But off the field, he would give his shirt off his back. Just the mouth big-hearted, nicest person that you’d want to meet, but he just did it his way, pretty much.”

Bob Welch won 27 games and was the AL Cy Young winner in 1990. Dave Stewart was 22-11 with a 2.56 ERA.

“Dave Stewart was actually, that next spring training, he was my roommate for spring training, and what I learned from him, just the components of, no matter what was going on around the outside noise or whatever, you knew that he was going to show up and give you six, seven strong innings, two runs or less, and keep you in the game. Just that look on his face that he gives you when he’s on the mound, the focus, the determination, that’s what I learned from him,” Harris said.

Another future Hall of Famer, Dennis Eckersley, was 4-2 with 48 saves, a (gulp!) 0.61 ERA – and 73 Ks and just four bases on balls in 73.1 innings that season.

“Dennis Eckersley, he was this laid-back, quiet, cool guy, kind of like the Pink Panther. You never hear him, but you see him, and he was just, always ready, no matter what. When the bell rings, he’s ready to go,” Harris said.

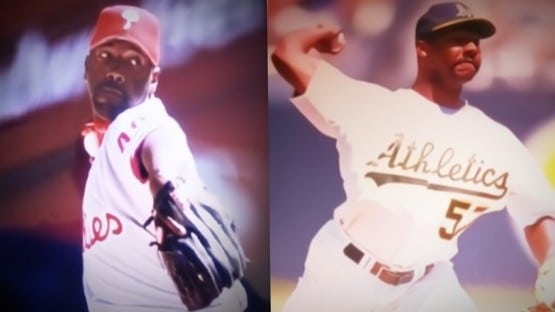

Harris, for his part, made 16 appearances, with one start, going 1-0 with a 3.48 ERA in 41.1 innings, 31Ks and 22 bases on balls, and a 1.111 WHIP for the 103-59 A’s, who repeated as AL champs, then lost in a four-game sweep in the 1990 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds.

Harris only made two appearances with the A’s in 1991 before getting sent down to Triple-A Tacoma, where he was 5-4 with a 4.99 ERA in 15 starts.

“In the middle of the ’91 season, I started to feel pain in my shoulder,” Harris said, “and the ’92 season, then end up getting surgery in ‘93 when I went to the Mariners, got it cleaned out, and the same thing started to happen a couple years later. Had to go to Taiwan in ‘95 to prove that I was healthy, to come back. Things started to feel better, then that’s when you start to see me being in the Major Leagues every year until ‘99.”

Harris got back to the bigs in 1996 with Boston, which called him up for the stretch drive after he’d posted a 1.46 ERA in 33 appearances at Double-A Trenton.

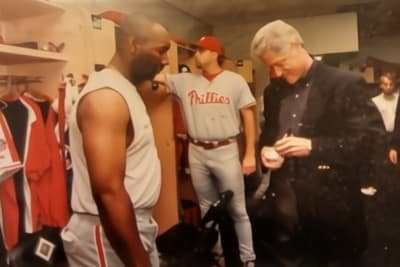

He made 50 relief appearances in 1997 with the Philadelphia Phillies, then split his 1998 between the Houston Astros and Triple-A New Orleans, and split 1999 between the Milwaukee Brewers and Triple-A Louisville.

Harris hung around into the 2006 season, pitching in independent ball, before finally deciding to call it quits, and making the move into coaching – serving as a pitching coach in the independent leagues, most recently working with the Down East Bird Dogs in the Frontier League.

“I had to make adjustments, because lot of stuff these guys do today, it wasn’t recommended us to do back then,” said Harris, citing as a for instance, “using a weighted ball was, like, taboo to us back then. A weighted ball would kill your shoulder. Now they build your shoulder.”

“The different kind of stretch routines with the rubber band, which I used, the rubber bands, and I used the five-pound weight, but I didn’t use the ball stuff that they do now, and that drive line technology that they have today. But it’s all fine. Everybody has a different routine that works for them,” Harris said.

Video: Pitching in the ’90s vs. pitching today

His career as a coach has him thinking of how life has come full circle.

Harris credits his success to the two coaches that he played for at Waynesboro High School – basketball coach Larry Leonard, and baseball coach David Huffer.

“My first experience with Coach Leonard was when I was probably in the sixth or seventh grade. And just because I used to follow high school sports back then, and I wanted to be a Waynesboro High School player in any sport as a kid, growing up in town, you knew all the players, grew up around them, but Coach Leonard had his high school varsity team to be the basketball coaches of the youth rec league back then, and he made a rule that if you score over 30 points, your team will lose. That taught me back then how to share the ball, how to be a good teammate, and that carried me on up through high school,” Harris said.

“Once I got to high school, I wasn’t considered a ball hog or anything like that. I knew how to play with others. I knew how to share the ball, because of that lesson taught me back then. Because all I thought was, just get the ball, beat the guy in front of you, score, and don’t worry about nothing else, and that wasn’t the correct way to play basketball. Coach Leonard taught me at a young age, and that’s something I carried along through my career and in life, that you can’t get anywhere in this world by yourself, you know, you got to have people around you, good people around you, good teams.”

Huffer, Harris said, “taught us hard work, practice hard, it will pay off, and that’s something that stuck with me all through my career, that you’re not going to get anywhere without hard work.”

“A lot of people thought, well, back then, that we just showed up and played. We worked harder as a baseball team in practice than we did in the game, so our games were easy, and that was something that he stressed, and he prepared the mental toughness, and that’s something that took them through my career from Coach Huffer,” Harris said.